username@email.com

username@email.com

In this section, we’ll continue to examine how students become readers, specifically how letter knowledge, mastering conventional spelling patterns, and other skills move them closer to comprehension and fluency. We’ll also review some more phonics terms that you’ll need to know.

Print surrounds us—on monitors, magazine, buses, televisions—and it can be difficult to realize what it might be like to take the first tentative steps into this world. However, it is crucial to familiarize students with the conventions of our language as it appears in print. Students should know the following:

Of course, as students’ skills develop, they may develop print awareness, which may include recognition of punctuation and other subtleties. At the outset of their reading careers, however, it’s enough for students to grasp the basics of the printed word.

If you weren’t aware of those basic concepts, you might not be able to recognize and intervene when your students exhibit characteristics of unhappy or struggling readers, including the following:

Conducting frequent formal and informal assessments of your students’ reading characteristics will inform your decisions about what to emphasize, as well as with whom. If you fail to recognize the needs of your frustrated readers, there is a strong possibility that their future reading habits will continue to diverge—in a bad way—from the healthy reading attitudes and habits of your happy readers.

Assessing a student’s facility with sight words is one common way to check on reading progress. There are several prepared lists of sight words, the Dolch list being one of the more popular. University of Illinois researcher E. W. Dolch assembled this list, which is divided by grade level. Here’s a sample:

| Dolch List: First Grade | Dolch List: Second Grade |

|---|---|

| after | does |

| lot | gave |

| once | those |

| take | their |

| walk | upon |

These lists can be used to guide assessments of students’ sight-word abilities and can be used throughout the school year.

At the outset of their careers as readers, young students may make a variety of mistakes, such as confusing the letters b and d or s and z. Other problems include skipping words, confusing “the” and “a,” using pictures to decode a word, and guessing the word based on its first letter.

Early on, a young reader’s fluency level will be such that they read word-by-word, and they will usually recognize mistakes in their own reading. As an instructor, it can be useful to help them formulate questions about what they’re reading. For example:

Student: “When the sun set, the house grew bark.”

Teacher: “Does that make sense? ‘The house grew bark?’”

Student: “No—houses don’t grow bark.”

Teacher: “Let’s look at that sentence again.”

Rereading is another effective strategy in smoothing out students’ decoding process, as well as helping them build fluency. Younger students will usually want to read and reread, and teachers can use this tendency to correct mistakes, build fluency, and increase comprehension skills.

Which of the following is characteristic of successful readers?

Choice B is the correct response. You’ll recall that letter-sound relationships are no problem for our successful readers, so they have learned that they can decode many words they encounter just by sounding out and blending the phonemes represented by the letters in the word.

Here’s a scenario: You’ve assessed your students’ reading habits and have identified one or more kids who aren’t yet comfortable manipulating phonemes. It might be tempting to continue at the pace of your middle group, but doing so will widen and perpetuate the nascent divergence we just talked about. Instead, you’ll need to conduct small-group lessons with your struggling readers in which you deal with phonemic awareness. How?

First, recognize that—even though this is phonemic awareness—this is something you can teach and that your students can learn. Rhyme and alliteration are, developmentally speaking, usually the most accessible to young children. For pre-kindergarten and kindergarten students, a number of daily activities that incorporate songs, poems, fingerplays, nursery rhymes, tongue twisters, and stories in anticipatable rhyme provide opportunities for explicit instruction in rhyme and alliteration.

During such activities, draw students’ attention to words that have the same ending sounds (rhymes) and words with the same beginning sounds (alliteration). Incorporate those skills throughout the day by asking students what words rhyme with new words you’ve learned, or with new students’ names, etc. Similarly, ask students to identify something in the cafeteria that begins with the /t/ sound, such as table, turkey, trays, etc.

Which of the following statements is true about phonemic awareness?

Choice D is the correct response. If phonemic awareness were not teachable, there would be a great deal more illiteracy in the United States.

Mastering rhyme and alliteration will make the phonological concepts of onset and rime more accessible to your students, but experts recommend swinging past sentence segmentation and syllable segmentation on the way to onset and rime. Such segmentation lessons lend themselves to kinesthetic learning, as you may ask your students to clap, slap, snap, or hop for each word in a sentence or for each syllable in a name or word.

The activities listed above—poems, fingerplays, etc.—are not done simply to take up time or because kids like them, although the former means you can squeeze lessons into transitions during the school day, and the latter is just plain fortuitous. When you’ve determined from some form of assessment the type of lesson your students need, you then choose the type of phonemic awareness activity that will facilitate your teaching objective.

Make sure that your instructional methods address specific goals—they need to be explicit and systematic. Click here for an example.

All of these phonological awareness competencies anticipate the most granular of the segmenting activities, the segmentation of words into discrete phonemes. It is this level of phonological awareness that people call phonemic awareness. Such progression from the most accessible to the most discrete phonological awareness competency is cumulative and natural.

Let’s take a look at one small-group activity. As you work through small-group lessons, keep a tally sheet that lists the specific letters you’re addressing, as well as the students in the group. This will enable you to record areas of continued need for each student, allowing you to group your students more effectively for subsequent instruction. Doing this will actually free you from aimless lessons and will be of greater benefit to the individual learners in your classroom.

Large letter cards for use by teacher (one of each letter)

Use these cards to activate the students’ prior knowledge of the letters and their associated sounds. After reviewing the letter names and sounds, model the objective for this lesson by stating the name of the letter d, identifying the photo of the dog on the photo array as representing a word that starts with d, and placing one of the small d letter cards on the photo of the dog.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Photo array for use by students (one for each student).

There are five pictures of things that start with d, five of r, and five of t.

Small letter cards for use by students (five of each letter for each student)

After you model how to use the tiles, let the group of students support each other in guided practice: Hold up the large letter card for any of the three letters and ask the group the letter’s name and sound. Then ask the group to identify a photo on the array of something that begins with that letter. Then ask the group to place one of the appropriate small letter cards on that photo.

Once it is clear that the group can perform the objective, clear the array, divvy up the cards again, and ask students to perform the objective independently, with their own sets of small letter cards and their own photo array, as you flash each of the large letter cards five times, in scattered fashion. Play the game, evaluate, and reteach, until mastery.

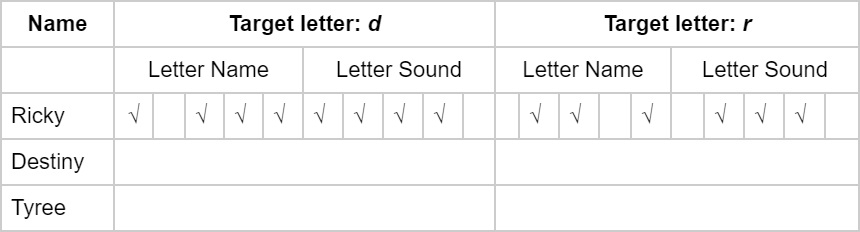

Now that the students can consistently match letters with their names and with photos of things that begin with the letters’ sounds, it’s time to evaluate students’ mastery of the objective of associating the written letter with its name and its sound.

The evaluation is always done on an individual basis. Choose two of the three letters from the activity and shuffle the ten small letter cards. Draw cards one at a time. The student is to identify the name of the letter and its sound. Use the tally sheet below to record student performance.

Each student is shown each of the ten small letter cards in the shuffled deck one at a time. He or she is to state the name of the letter, as well as the sound of the letter. Mark the corresponding space for each correct response. If the student does not respond correctly, leave the corresponding space blank. The goal is at least four correct responses out of five chances. Ricky needs some more practice with the letter “r”.

For teaching letter-sound associations, there are many visual aids and manipulatives you can either make with the students or buy commercially. If you have several different types of programs, letter manipulatives, or reading instruction methods available, you can judge the relative effectiveness of each one to the others, based on the results of your ongoing progress monitoring.

Continuous progress monitoring helps the teacher do which of the following?

Choice A is the correct response. Continuous progress monitoring allows the teacher to marshal his or her resources more wisely, to group students for instruction appropriately, and to determine whether instructional methods are effective.

Which of the following is another way to say “explicit and systematic”?

Choice C is the correct response. The explicit part of the phrase refers to the clear relationship between the activity and the objective it’s planned to teach. The systematic part of the phrase refers to the teacher’s intention for teaching the lesson, as will be measured when the student is given the opportunity to perform the objective independently. Assessment informs the lesson and measures its effectiveness.

It is likely that students will gain some understanding of the mathematical concept of one-to-one correspondence around the same time that they are being taught phonological awareness lessons. If you teach first grade and have noticed that a student isn’t catching on to the segmenting activities, it may be that he or she hasn’t grasped one-to-one correspondence yet. Such students will not be able to transfer manipulatives from one container to another while counting each manipulative aloud. That is, they do not recognize that each number corresponds to one and only one of the manipulatives. It is apparent that lacking that ability would have a negative effect on students’ segmenting efforts in phonological awareness activities.

Which of the following phonological awareness skills represents “phonemic awareness?”

Choice D is the correct response. Remember that phonemes are the irreducible elements of spoken language. When students recognize these individual sounds and are able to segment them, drop them, and add them, those students are phonemically aware.

First, monitor each student’s phonological awareness to verify whether he or she is on track with the objectives you have set. In the course of your monitoring, you will be able to identify the specific students who need further practice with the assessed objectives. You can also use the results of your monitoring to determine the type of further practice that is needed; you’ve asked about letter-sound associations, so we’ll say that is a need for several of your students. Ideally, you will also have determined from your monitoring which specific letter-sound associations these students require more work with.

When providing additional instruction, work with small groups of students showing similar needs. Whole-group instruction is least effective for reviewing objectives needed by only a few students, as those who have already mastered the objective may become bored and disruptive or may be overeager to demonstrate what they know, giving the target students little incentive to apply themselves to the lesson. One-on-one instruction sometimes puts students ill at ease; but small-group instruction allows you to focus on specific objectives with a small number of students, while providing a sense of insulation that encourages each student to participate.

Like phonics instruction, vocabulary instruction works best when it is systematic and explicit. And, while “explicit vocabulary instruction” can conjure up images of word lists, dictionaries, and weekly quizzes, it doesn’t have to be boring or rote. The English language has seemingly endless twists and turns, and these can be used to engage students more directly than memorizing definitions from the dictionary. For example, you could dig a little deeper than the dictionary in examining the word “gave” in the following sentences:

Marcus gave James $199.

John gave his wife a kiss.

She gave her patient an injection.

The troupe gave an excellent performance.