username@email.com

username@email.com

In this lesson, you will learn comprehension strategies for the interpretation and analysis of literary texts, including how to identify meaning, structural elements, themes, and genre. We’ll start by looking at some organizational schemes that writers use to convey information most effectively.

At this point, you should be familiar with some common organizational structures authors use to convey information, including cause and effect, compare and contrast, problem and solution, sequencing, classification, and generalization. You should also be aware that informational text makes use of a lot of visual elements, such as charts and graphs that students must be able to identify and interpret to fully understand a particular text.

We mentioned at the beginning of this module that our culture is one of information and one has to be able to absorb an extraordinary amount of information on a daily basis. Whether it’s through print, radio, television, or the web, every waking moment is, essentially, an opportunity for someone to tell you or sell you something.

Students, like all of us, must be able to quickly recognize common types of unreliable information if they’re to make informed decisions about their lives and the world around them.

Earlier we discussed several organizational structures authors use to convey information. Authors often use persuasive techniques within these structures to build an argument for or against a particular topic or idea.

| Technique | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Bandwagon | Attempts to convince you to do or believe something because everyone else does. | The smartest shoppers motor on over to Big Tire. |

| Testimonial | Attempts to convince you of worth because someone famous endorses a product or idea. | Aldous Huxley for Soma… |

| Emotive | Uses words or images that appeal to the reader’s or viewer’s emotions. The appeal may be to positive emotions, such as success, or to negative ones, such as fear. | What would you do in the event of an emergency? Would your family be protected? Buy SaneSafe. |

| Everyday People | Ordinary people convince you they can be trusted because “they’re just like you.” | As a teacher, I use a lot of chalk—and if there’s one that’s dependable, it’s Super Chalk. |

| Rich and Famous | This technique suggests that you can be like the attractive, wealthy people who use this product. | Of course you’re worth Money-Suds! |

One way to teach students to identify persuasive language is to have them examine the logic of a particular idea or argument and use graphic organizers to evaluate the reasoning.

The poet Muriel Rukeyser once said, “The universe is made up of stories, not of atoms.” Though scientifically inaccurate, the sentiment behind Rukeyser’s words is true enough: our realities are constructed from stories—historical, cultural, and personal narratives—that help us define ourselves and understand the world around us.

Whether it’s a fable about a little girl attempting to visit her grandmother or an epic sonnet that details the journey of a fictional hero, narrative texts convey stories that ignite our imaginations and give us insight into thoughts and feelings beyond our own experience.

Comprehension strategies encourage careful reading that allows a student to interpret narrative texts beyond literal meaning. By asking questions before, during, and after reading, students are able to make connections between their own life and the life of the story. Summarizing and making generalizations supported with examples from texts encourages deep processing that is essential to developing language skills.

Learning to interpret story elements such as plot, theme, characterization, setting, and point of view will help students understand the building blocks of a story and allow them to identify how an author uses structure and language to convey meaning across a wide variety of genres.

Take a look at the chart below to review some key terms before we discuss these story elements in further detail.

| Element | Definition |

|---|---|

| Plot | The sequence of events that take place in a story. There are five components to plot: conflict, rising action, climax, denouement, or falling action, and resolution. |

| Theme | The underlying message of the story. Theme is closely related to main idea but is usually more global in scope. Characterization, plot, setting, and point of view all contribute to a story’s theme(s). |

| Character | Characterization is made up of three elements: appearance; personality, and behavior. |

| Setting | Time and place. Details that describe setting might include weather, time of day, location, landscape, and even furniture. All of these things can contribute to the understanding of a scene. |

| Point of View | Point of view refers to the narrator of the story. The most common points of view are first-person, third-person limited, and third-person omniscient. |

At the heart of every story is the plot, or skeleton—the sequence of events that takes place from beginning to end. There are five components to plot:

Writers vary plot structure depending on the needs of a story. These basic elements are the building blocks of narratives and can be found in every story.

One way to have students learn simple story structure is to familiarize them with a wide variety of fairy tales, fables, myths, folktales, and legends as these stories tend to be linear in nature and contain predictable outcomes that will allow students to recognize how an author uses plot to frame sequential events.

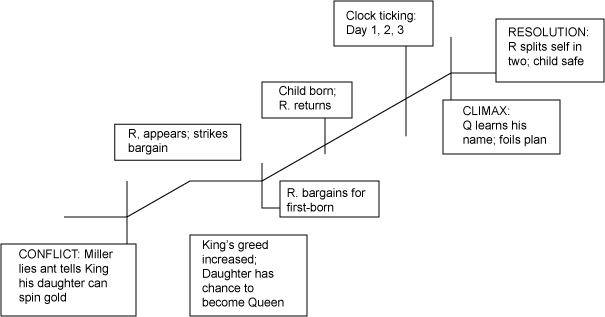

Let’s take a look at how the elements of plot combine to create the classic tale “Rumpelstiltskin.”

“Rumpelstiltskin” is often interpreted as a story of good triumphing over evil. Though this particular tale begs some larger questions that we’ll examine when we discuss characterization, in terms of plot, “Rumpelstiltskin” follows a linear pattern that we’ve mapped out below.

Fables, folktales, fairy tales, myths, and legends are short stories generally considered as teaching tales in the sense they often provide us with a moral or lesson. Many of these tales have been passed down through an oral tradition of storytelling that has led to interpretations across cultures. Familiarizing students with tales and legends from around the world not only provides students with a unique insight into a variety of cultures but also helps them identify universal themes and recognize the impact of folklore on our shared history.

You should be familiar with the similarities and differences of these types of stories as outlined in the chart below.

| Term | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Fable | A fable is a very short story that tells us a moral or lesson. A fable very often has an object or animal (with human characteristics) as the central character. | Little Engine That Could, Aesop’s Fables |

| Folklore | Fictional stories that generally stem from an oral tradition and usually have several interpretations across cultures. Folklore contains the beliefs and customs of a region or country. | Santa Claus, The Pied Piper |

| Fairy Tale | Fairy tales are a type of folktale. A fairy tale may use elements of royalty, magic, enchantment, and the supernatural. | Little Red Riding Hood, Sleeping Beauty |

| Myth | Myths are regarded as true stories within a culture and often use the supernatural (gods, goddesses) to interpret natural events. | Cupid and Psyche, Pandora’s Box |

| Legend | Legends are stories based on a real-life hero and his or her mighty deeds. Usually, humans, not gods, are the main characters in legends. | Robin Hood, Paul Bunyan |

Before we move on to the elements that move a story beyond literal meaning, let’s take a look at how the information we’ve covered might be presented in a test question.

“Rumpelstiltskin” was written by the Brothers Grimm and is an excellent example of a

The correct answer is D. Though “Rumpelstiltskin” has many of the attributes we associate with folklore, fairy tales are written tales, often original or retold stories with a fixed text and a single named author (in this case, the Brothers Grimm). Like fairy tales, folktales are nonspecific in terms of setting and often begin with the familiar “Once upon a time.” Both types of stories frequently have a plot in which good overcomes evil. Characters perform a task, using their own ingenuity and perseverance, often aided by magic and trickery.

Which is an example of the falling action in “Rumpelstiltskin?”

The correct answer is B. The falling action, or denouement, in a story takes place in the events that follow the climax, which in this case is the confrontation between the queen and Rumpelstiltskin. Sometimes the falling action in a story is very brief, as it serves more or less as a setup for the resolution. Denouement has French origins and essentially means “to untie.” All of the knots of the plot are untied, and the situation is resolved. Take the plot of The Wizard of Oz: the falling action happens when Dorothy gets back to the Emerald City, sees the Wizard, and is eventually sent home by Glinda.

Themes are perhaps the most difficult story element for new readers to identify. Themes are often inferred or implied, and readers must analyze all the elements of a story: plot, characterization, setting, and point of view, in order to interpret the one or many themes a particular text may have.

Now that we’ve mentioned Dorothy, let’s look at some of the themes in The Wizard of Oz as examples. The most obvious theme is repeated as an incantation at the story’s climax: “There’s no place like home.” Dorothy tells us, in essence, to appreciate the gifts we have and that the grass is not always greener on the other side. Other themes force us to dig a little deeper—but not much. The theme of appearance vs. reality can be found throughout The Wizard of Oz. Take, for example, the characters of the Scarecrow, the Cowardly Lion, and the Tin Man, who show us that individuals are ultimately defined by their integrity and not their outward appearance. Another example is the wizard himself, who is just a normal man hiding behind a powerful facade. In fact, the entire text of The Wizard of Oz supports this theme given the fact that Dorothy’s adventure in Oz was all just a dream.

Earlier we touched on the subject of universal themes found in folklore from around the world. One such theme, the hero’s quest, is evident in the text of The Wizard of Oz as well. The archetypal hero can be found in texts throughout history—from Hercules to Harry Potter. Generally born to adversity, heroes have gifts or abilities that enable them to overcome all odds and perform extraordinary deeds. These powers are sometimes not only of the body but also of the mind.

You may want to have students identify tales across texts that embody the hero’s quest and to compare and contrast the wide variety of interpretations. Though heroes come in all shapes and sizes, they share a common trait in strength of character, despite their respective goals.

No story, no matter how interesting, will come to life without good characters. Well-drawn characters give us access to the thoughts and emotions of a story and allow an author to represent a variety of experiences within a text. Characters embody plot. As we saw in The Wizard of Oz—it’s not just a girl who goes to see a man; it’s Dorothy who goes to see the Wizard. Understanding the components of characterization is crucial to our interpretation of any narrative texts.

Characterization is made up of three elements:

Authors use characters to move the action of a story forward as well as convey deeper thematic content as we saw in the previous examples. Sometimes characters are what they appear to be. Good and evil have been locked in opposition throughout history so archetypal heroes have archetypal villains. Often, however, an author will use characterization to upset our expectations: heroes are flawed, and villains have a change of heart.

In other instances, characters leave us with more questions than answers, and we must analyze their actions to divine deeper meaning. Case in point: “Rumpelstiltskin.”

Let’s move back to the story briefly to examine how characterization moves the plot and supports some underlying themes.

| Character | Appearance | Personality | Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rumpelstiltskin | “manikin;” perhaps a demon of some sort, not quite human | proud, gloating, manipulative; values life (child) over riches; takes pity on queen | takes advantage of daughter; gives her the chance to get out of the bargain; destroys himself with anger |

| Daughter/Queen | pretty, initially poor, a victim; later wealthy | lies for her own survival; agrees to give her firstborn child to R.; thinks she’ll get away with it | wants to protect her child; enlists help of others to outsmart R.; toys with him before she reveals his name |

| Miller | poor, a peasant | insecure; values status over family | puts his daughter in danger to make himself look better |

| King | wealthy | values money over love | unsympathetic, cruel |

There’s no denying that Rumpelstiltskin is a dark character and out for no good, but it’s interesting to note that although he’s the only character we view as evil, he is also the only character who demonstrates compassion. Aside from the queen’s desire to protect her child, every action of the rest of the characters in the story is negative. Every character lies or values money over life and love but Rumpelstiltskin. His motives, though perhaps evil, are honest. Though at first glance the story seems straightforward, the author’s use of characterization provides us with a fairly complex story that leaves us with a central question: who is this “manikin” exactly, and what does he represent?

If we examine the motivations of the characters, we see that greed, status, and personal gain top the list. Rumpelstiltskin plays on these desires. He is small, not quite human, a character who lurks in the shadows and dances in the outermost regions of the woods. We might view him as the devil or a demon, or perhaps the dark part of every human nature. In this sense, “Rumpelstiltskin” can be interpreted as a cautionary tale that warns us of the hazards inspired by greed and boasting.

Every action of every character in a story moves the plot forward. It is through characters that the drama of a story is revealed. What a character does, thinks, and says determines the outcome of a story, and, just as often, setting determines his or her behavior.

Setting is the time and place the action of a story unfolds. Authors use specific details to create an environment that provides us with information about characters, plot, and thematic meaning. Setting might include details about the weather, time of day, location, landscape, era—even the particulars of a given room (chipped paint, peeling wallpaper, an unmade bed) paint a portrait that allows us to visualize the world our characters inhabit.

Point of view refers to the narrator of the story. Writers use point of view as a device to achieve a certain tone or style or to relate a desired perspective of a story. The most common points of view are first-person, third-person limited, and third-person omniscient.

Let’s take a look at how some of these elements combine in Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper.

Notice how Twain uses setting to underscore the disparity between the boys and shape our expectations of events to come. With the details in this opening chapter, we not only have a clear image of the time and place (London in the sixteenth century) but also of the circumstances surrounding the boy (Edward Tudor, long-awaited son of Henry VIII—and the reason he had so many wives). Twain’s use of a third-person omniscient narrator gives him the ability to tell the story from a variety of perspectives: across characters and across time.

In this next section, we’ll review some specific devices that authors use to shape their language. We’ll also see how the form that authors use influences the effect on the reader.

At this point, you should be familiar with the basic literary elements of narrative text including plot, setting, and point of view, and how authors use these elements to convey underlying meaning or themes. You should also be familiar with the similarities and differences between fables, fairy tales, folktales, myths, and legends.

Precision of language is key to an author’s craft. An author’s word choice determines whether a story is simply good or great, full of surprises or fraught with confusion. Word choice and description not only set the tone or mood of a particular story but also relate important information to the reader about setting, plot, character, and ultimately theme.

Authors use dialogue to convey any and all information about a particular character’s age, culture, education, gender, personality, historical era, beliefs, etc. Dialogue brings a character to life and makes a story believable.

Let’s look at the opening of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Diction refers to the way a character speaks. Huck speaks in a very particular diction that is appropriate to his age, lack of education, historical time period, and upbringing. Twain uses Huck’s dialogue purposefully to underscore the effect of Huck’s awakening at the end of the novel.

Authors use imagery and symbolism to create a certain mood in a story. To borrow another example from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, we see the river throughout the book as a constant symbol of freedom, independence, and life in the wild. The river typifies the life Huck wants to live and the freedom due Jim, and by extension, all slaves in the South.

Allegories are stories or poems in which an author uses animals or objects to represent moral, political, or religious meaning. In Animal Farm, George Orwell uses animals to critique the tyranny of totalitarianism and bases many events in the book on the Soviet Union during the Stalin era.

Figurative language refers to an author’s use of a word or phrase that is not intended for literal interpretation. You’ll want to be familiar with the different types of figurative language as outlined in the chart below.

| Term | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Alliteration | Refers to the repetition of usually initial consonant sounds in two or more words or syllables | “The sweet smell of success” |

| Hyperbole | Refers to a phrase of grandiose exaggeration, usually with humor | “I’m so hungry I could eat a horse.” |

| Metaphor | Refers to an author’s use of comparison of two things by using one kind of object in place of another to suggest the likeness between the two | “My dog, Rainbow, has a cast-iron stomach.” |

| Personification | Refers to an author’s use of language that endows objects or nature with human qualities | “The sun smiled as we drove through the sleeping mountains.” |

| Simile | Refers to an author’s use of like or as in a comparison | “My dog, Rainbow, is as pretty as the morning sun.” |

Authors use figurative language for a variety of purposes. As we discussed with the example of symbolism, figurative language can provide a reader with subtext that hints at deeper meanings in a story and can also provide ornamentation that supports and creates a desired mood or response.

Though personification, metaphors, similes, and alliteration are used across a wide variety of texts, poetry, perhaps most notably, makes use of figurative language for its aesthetic qualities and its ability to convey deep meaning with economy.

Literary genres are types of writing that each employs unique conventions. At the most basic level, literary genres are divided into poetry, prose, and drama, with sub-categories within those classifications.

Authors use specific genres to gain a desired effect. In literature, form does indeed equal function. Students should be aware of the distinctions that differentiate one facet of literature from another as well as how these genres have developed over time and across a variety of cultures.

| Genre | Definition |

|---|---|

| Poetry | Poetry is literature written in metrical verse. Literary elements associated with poems include:

|

| Play | Plays are dramatic works intended for performance by actors on a stage, often described in terms of types, such as classical, tragedy, or comedy. They are generally written in one to three acts and convey action through the use of dialogue with minimal stage directions. Plays often interact with an environment (stage, space, a live audience) to convey meaning. |

| Prose | Prose writing is fiction or nonfictional works that attempt to mirror the language of everyday speech. Prose can be any length—a short story or novel. The word prose comes from the Latin prosa, meaning straightforward and reflects the type of writing this form embodies. |