username@email.com

username@email.com

In the upcoming pages, we’ll examine basic ideas about phonological and phonemic awareness. We’ll review the basic terminology of the discipline (morphology, graphemes, orthography, etc.) and touch on some ideas about how to instruct students in phonics.

At the most basic level of alphabetic basics is the Alphabetic Principle—the idea that sounds can be represented by symbols. We’ll explore this root concept here, as well as how it applies to teaching young students to read with fluency and comprehension.

As a discipline, phonology may have more than its fair share of jargon. Let’s review some of the key words.

| Term | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Phonological | Recognition of the distinct segments of spoken sound: words, syllables, and phonemes | Let’s take the word kitty. Students should be able to recognize that the word is composed of four distinct sounds, or phonemes: /k/ /i/ /t/ and /e/ |

| Phonemic Awareness | Recognition of phonemes, ability to segment words into constituent phonemes, ability to blend phonemes and substitute phonemes to make new words | Students should be able to recognize and recombine phonemes to make new words. For example, a student exhibits phonemic awareness by recognizing that the /k/ in kitty can also be used to begin the word call or can’t |

| Phoneme | Smallest unit of sound | /s/, /ch/, /f/, /e/, /sh/ |

| Syllable | A word or distinct segment of a word that is naturally pronounced in a single, uninterrupted vocalization | cant can•ti•le•ver chalk chalk•i•er e•ryth•ro•my•cin grid•dle |

| Voiced (and unvoiced) consonants | Voiced consonants make your vocal cords vibrate; unvoiced do not | Voiced: b, d, g Unvoiced: p, t, k |

| Morpheme | Smallest unit having meaning: base words, prefixes, and suffixes | biology {bio-}=”life” {-logy}=”science” biologist {-ist}=”one who practices” chokers {choke}=”obstruct the trachea” {-er}=”one who [chokes]” {-s}=”more than one |

| Phonics | Study of relationships between sounds and their written form | In the word rock, the first letter, the r, makes the /r/ sound. The o sounds like ahh, and the ck sounds like /k/. You’ll see the ck after short vowel sounds, like in rock, sick, tack, luck, neck, and chick, but not after long vowel sounds, like in lake, nuke, poke, hike, and cheek. Note too that in words that end with a “vowel + consonant + e” combination (VCE), the vowel is long, which means that it sounds like its name: ay, ee, eye, oh, you. |

You’ll be able to link back to this table down the line, but for now let’s look more closely at some of the key terms.

If we smile and press the tongue to the back of the roof of the mouth and force a burst of air over the stubborn tongue, we’d have the phoneme /ch/. (The slashes tell you that we’re referring to a single phoneme.) You can’t break /ch/ down any further if you still want the sound /ch/, as in the word choke. Phonemes, then, are the smallest elements of spoken language.

The fact that /ch/ contains two letters is a little frustrating for most of us, but it just happens to be a limitation of the English alphabet that we don’t have a single, unified symbol—a letter, or grapheme—to represent the single, unified phoneme we hear at the beginning of the word choke. So “ch” is also a grapheme, even though it’s two letters. And since these two letters form a single phoneme, we call it a digraph. The digraph that represents the “ch” sound is /ch/.

Here’s how this information may be presented in a test question:

Which of the following represents the smallest element of spoken language?

The correct answer is D. If it can be uttered, it’s composed of one or more phonemes, plain and simple. Choice A, grapheme, is the written representation of a phoneme, and is usually the letter (or letters) that make that sound. If the grapheme contains two letters, then it is a diagraph—choice C. Choice B, morpheme, is the smallest unit of a word that has meaning. You’ll find out more about morphemes in a minute.

Every little sound of every word ever spoken in any language is a phoneme, though each language makes use of a different number of phonemes in order to say what they need to say. For instance, native Spanish speakers have no problem trilling their “r”s, as the trilled “r” is an important Spanish-language phoneme. Many English speakers, however, find it difficult to produce a trilled “r,” as evidenced by our one-time fascination with repeating a declaration that such-and-such national brand of potato chips has “rrrridges.”

While it may seem clear that graphemes match up perfectly with their respective phonemes, English is a weird language. Consider this group of graphemes:

ghoti

Of course, this is an extreme example, and goes against all our spelling conventions, but this group of graphemes could represent the animal in this picture:

gh represents the phoneme /f/, as in the word enough

o represents the phoneme /i/, as in the word women

ti represents the phoneme /sh/, as in the word nation

Keep in mind that we’re talking about “phonemic awareness.” The “awareness” part is key because our short-term goal is to make students conscious of the fact that language is made up of a finite number of phonemes. They can recognize these phonemes, distinguish one from the next, break them apart, and make new words by switching one or more phonemes for others. Once kids have mastered the complexities of onset and rime, syllabication, and phoneme segmentation, they’re ready to match those familiar sounds to the letters that represent them; and, of course, that will determine whether they’ll be successful readers and, consequently, successful students.

At this point, you should know about the alphabetic principle and how graphemes and phonemes come together to produce the language that we share. You should also have a basic grasp of the specialized terminology of the discipline and be able to answer questions about phonemic awareness.

Let’s move from sound to meaning. A morpheme is the smallest unit of language that creates meaning. We could combine /ch/ and /o/ and /k/, in that order, to form the word choke. Because we need all of that word to convey any aspect of its intended meaning, the word {choke} is a morpheme. In the word choker, the {-er} at the end is also a morpheme. Why? Because {-er} conveys meaning all by itself: It tells the listener that we’re referring to one who does the first part of the word; that is, one who chokes. Adding yet another morpheme, the plural {-s}, now tells us that there are at least two who choke. Like the slashes used to indicate phonemes, brackets are used to indicate morphemes.

Which of the following is a morpheme?

The correct answer is B. Though you’ll see {–nk} at the end of numerous words, it does not have a meaning of its own at all. It only provides meaning in the sense that it might complete a morpheme, as in trunk or stink, but it’s neither interchangeable nor portable. The same applies to answer choices A and C. Choice B is the prefix that adds a negative denotation to such words as amoral, apolitical, atheist, and apnea.

Which of the following words begins with an unvoiced consonant?

Did you say C? Must be kismet. Remember that unvoiced consonants are the ones that don’t move your vocal cords when they’re pronounced. Among these choices, only the /k/ phoneme doesn’t vibrate those cords. Click back to the chart if you want to review other unvoiced and voiced consonants.

Let’s try another one.

Examine these words:

harpist, escapist, cellist, linguist

In each case, the –ist ending means that this person does something, such as plays the harp, escapes, plays the cello, or works with languages.

The –ist ending is a

Answer B is correct. Morphemes are the smallest units of language that can have meaning; here, the –ist suffix means “one who practices.”

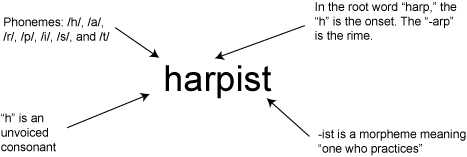

Sometimes it’s helpful to analyze several different components of one word. Let’s look at the word harpist. We’ve labeled some important parts of this word.

Making students aware of phonemes and how they work together to create morphemes is important, but it’s only a means of teaching them to be strong readers and effective writers. Learning phonemes and how they work is like getting familiar with the parts of the engine that make the car run. Now, let’s look at how to get students behind the wheel.

In practice, most teachers probably use a hybrid of different phonics instruction styles. However, the one backed by most researchers is synthetic phonics. In some ways, we’ve been talking about this style of instruction already in this course. Synthetic phonics instruction begins by teaching aspiring readers the basics of grapheme-phoneme relationships. Students then learn to blend these patterns into words.

Some key words attached to this method are systematic and explicit—you’ll hear these a lot when studying phonics instruction. Successful modes of instruction are deliberate and measured—systematic. They are also clear and to the point—explicit.

In the classroom, a teacher may determine a group of letters to teach the students, for example, “b,” “a,” “t,” and “c.” This instruction may take different forms, but notice that one component is already in place: explicitness. Nothing is left to chance here—the teacher has set a definite course of action. Teaching these letters may take a variety of forms: songs, oral games, chants, call-and-response activities, and so on.

Once the students have learned these sounds–/b/, /a/, /t/, and /k/–the teacher will systematically explore simple words that employ these phonemes. Cat and bat are obvious choices, and the students will readily blend these phonemes to produce those morphemes.

Another hallmark of synthetic phonics instruction is practice. The students will regularly be asked to practice the phonemes and graphemes that they are learning. The teacher will systematically employ writing exercises, customized reading texts, and other methods to ensure that the students get enough rehearsal time with their new skills.

You should also be familiar with various techniques used by the teacher and the students in phonics instruction, including blending and segmenting.

Once students know a group of phonemes, they can combine these to form words. This is called blending. Remember that teachers will be explicit and systematic in presenting groups of phonemes, so they will retain a certain measure of control over the blending technique.

Students (or teachers) practicing segmenting will break a word down into the phonemes that comprise it. For example, segmenting the word “tap” would entail drawing out the phonemes /t/, /a/, and /p/. Teachers and students can demonstrate how to segment the word “tap” by moving each letter away from the others while saying the sound that corresponds to it. Tying the phonemes to the graphemes via one-to-one correspondence boosts the phonemic awareness skill of segmenting up to a phonics application.

More closely associated with reading, decoding means using phonemic knowledge and prior knowledge of spelling conventions to read a word. Experienced readers decode at a rapid rate, but early readers use blending to slowly decode words, usually one at a time.

While synthetic phonics is the most preferred method, you should also be aware of the other techniques with which it’s combined. Some of these are used as stand-alone methods as well.

Since it’s such an intuitive approach, you’ve probably been using analogy phonics all along. In this approach, you discuss a word that is already familiar to your students, thereby activating prior knowledge. Then you simply have them make a textual connection between a new word that is very closely related to a familiar word.

For example, you might want to introduce the word “prank.” Fortunately, you’ve already addressed the concept of “bank” during your discussion of communities, and you had the presence of mind to tape the word “bank,” neatly printed in large letters, on the Word Wall. You simply point to the word, asking a student to read it. She correctly reads, “bank.”

You ask another student to state the last three letters of the word, and he correctly says, “a, n, k.” You then ask that same student to state the last three letters of the new word. Once he does, you remind the students that many words that end with the same letters also happen to rhyme.

Next, you point out that both words end in “ank.” You then ask the question: “If we drop the /b/ and add /p/ and /r/ to the beginning of the word, what does it sound like?” This should elicit the word “prank.”

Another approach to phonics that capitalizes on prior knowledge is called analytic phonics. This is similar to the analogy approach, but with a small difference. In analytic phonics, you’d do everything as it was done in the analogy approach described above except for the way you introduced the “p” and the “r” at the end of the lesson. With analytic phonics, you’d refer to a word you’d previously taught that contains the “pr” blend, such as “pretty.” You’d ask the students to say the word that starts like “pretty” and ends like “bank” in order to elicit the word “prank.” Notice that you’re not discussing individual phonemes outside the context of a real word, as in analogy phonics.

In some circles, the least popular approach to phonics instruction is embedded phonics. The drawback many see with this approach is that it is more or less incidental; that is, it is not systematic and explicit. However, if you happen to encounter a word such as “prank” in your reading of a learner-appropriate text, you’re free to unleash the power of the analogy or analytic approach in order to address this word. The only difference is that you’re addressing a word type as it happens, rather than as an explicit strategy in anticipation of encountering such a word.

An approach that is more successful with truly phonemic languages (such as Spanish) is phonics through spelling. Despite the occasional frustration with words like one, scents, gnome, and knock; and, of course, the less frequent bough, rough, trough, and through, this is still a fun and useful way to get from spoken English to written words. After you have the students break words up into phonemes, they get to pick out letters to match those individual phonemes. Then they put them all together and read the blended concoction.

In this approach, students are actively engaged in determining which letters to choose in order to represent the sounds in their words. This, of course, corresponds to mandated and useful learning objectives.

Try some questions about different types of phonics instruction:

Which of the following phonological awareness skills is integral to analogy phonics?

Answer D is the answer we’re looking for. Choices B and C are similar, and neither of them is integral to analogy phonics. Choice A, of course, is not integral to analogy phonics, as we are concerned with what’s happening within words, not with what’s happening with large groupings of them.

What is the primary difference between analogy phonics and analytic phonics?

Answer D is the correct response. Choices A and B are both true statements, but they are true for both approaches; no difference is described. Choice C is simply a false statement. Choice D points out the difference between these two approaches, namely, that analogy phonics employs individual phonemes to complete a word that is partially decoded by analogy. Analytic phonics does not employ phonemes independent of whole words.

Which of the following explicit phonics instructional methods begins with a spoken word and ends with a written word?

Answer D is the only choice that is explicit, begins with a spoken word, and results in a written word. The resultant word may or may not be spelled in the conventional manner, but this is still systematic instruction toward the objective of identifying letters that relate to specific sounds.

It’s important to note that phonics does not equal reading, just as dribbling and passing a basketball does not equal playing basketball. Good phonics instruction gives students the ability to establish a solid connection to the Alphabetic Principle and starts them on their way to decoding.

Regional speech differences, different dialects, speech impediments, and other issues result in different needs for different students. As a teacher, you will have the freedom to emphasize or combine teaching strategies in order to meet the needs of every individual learner in your class.

Systematic instruction should include significant amounts of time for students to practice segmenting and blending phonemes, matching graphemes with phonemes, and other crucial skills. Explicit instruction should include purposeful lessons in which the teacher begins with a specific objective, models how to perform the objective, and allows students to attempt the objective themselves.