username@email.com

username@email.com

These next pages will review some basics of America’s civic life. This section will also expand on ideas about the United States government that have appeared in previous lessons.

Prior sections covered the colonial times through the 20th century by reviewing some of the key events that have shaped our country.

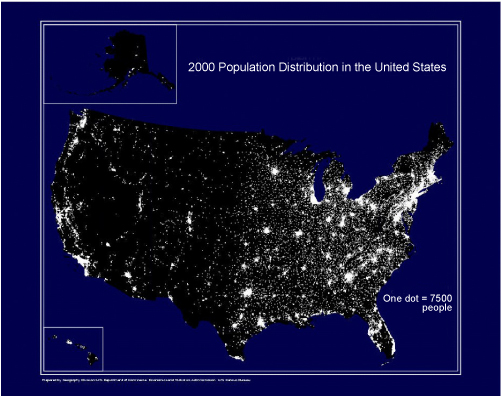

The United States of America comprises some 324,985,873 people. And, while its political institutions are well-established and seemingly timeless, political life in the U.S. (like all places) is constantly evolving. Let’s examine some of the major antecedents of America’s representative democracy.

The Athenians had one of the first forms of large-scale democracy. In the 5th century BC, citizens came together to pass laws, try crimes, and decide other important issues facing the city-state. However, in this case, a “citizen” meant a male who had completed his military training. Women, resident aliens, and slaves were not permitted to assemble and voice their opinions.

The Romans called their system of government a republic from the Latin res (“thing”) and publicus (“of the people”). As the Roman Empire expanded, the more far-flung citizens were left out of the process since the decision-making process was carried out at the forum in central Rome. Although deeply flawed from our modern perspective (again, the only citizenry who had a say were privileged men), the Romans did give us the Senate, an enormously powerful political body who were indirectly elected.

The Magna Carta, or “great document,” was another move toward democracy. The controversial King John ran afoul with the Church and was excommunicated. To return to the Pope’s good graces, he made concessions that turned the barons of England against him. He then conceded absolute power by signing the Magna Carta in Runnymede in 1215. This made even the king bound by English law.

Citizens of the United States are subject to the powers of the three major branches of the federal government: the executive, the legislative, and the judicial.

The legislative branch is established by Article One of the Constitution and sets forth the idea of the Congress, which comprises the House of Representatives and the Senate. Each state elects members to the House of Representatives based on its population; however, each state elects two members of the Senate for a term of six years. Article One also enumerates the powers of Congress, which range from the regulation of international commerce to the establishment of new post offices.

The judicial branch is established by Article Three. It states that:

The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behavior, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services a Compensation which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office.

Supreme Court judges are appointed by the executive branch and confirmed by the legislative branch. Note that judges hold their positions “during good Behavior” (a phrase that is usually interpreted to mean for as long as they’re alive).

The executive branch is established by Article Two and calls for the election of a president and vice president. The president wields enormous power but it is checked by the legislative and judicial branches. For example: the president is the supreme commander of the US military but cannot declare war without congressional approval. As we saw in previous lessons, this system of checks and balances is a crucial feature of the constitutional system.

In the late 1780s, the Constitution’s ratification was fraught with controversy. On one side were the Anti-Federalists, who opposed the stronger centralized government that the Constitution would create. They were opposed by the Federalists, a group which included Alexander Hamilton. The Federalists were proponents of the Constitution and attempted to persuade the citizenry through a series of articles that have come to be known as the Federalist Papers.

The Federalist Papers still serve as a guide to many judges in interpreting the intent of the US Constitution.

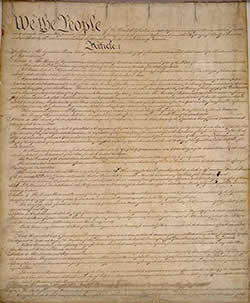

The US Constitution

The U.S. Constitution signed in 1787 did not contain a list of citizens’ rights, an exclusion that quickly brought criticism from the Anti-Federalists who argued that the exclusion of rights was proof that the Constitution’s framers wanted power. On the other side, there was also concern from some Federalists who thought that a specific list of rights would be interpreted as the only rights a citizen possessed.

However, the majority of Federalists saw a great need for a list of rights, and James Madison took up the task in the summer of 1789. Using state charters and other writings as models, he submitted his draft to Congress, and it was passed in December of that year.

While the Bill of Rights comprises a group of amendments, it is an essential piece of the US Constitution itself. Click here to read more about the Bill of Rights.

The history of the United States is full of notable people and events—the Founding Fathers, the birth of the country, and the crucial developments in the evolution of our representative democracy. Below are a few examples of America’s historical figures and milestones.

Born a slave in Maryland, Douglass escaped to the North in 1838 and began his career as an abolitionist, writer, and intellectual. He advised presidents (Lincoln and Grant), served as the marshal of the District of Columbia, and penned the classic memoir, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. He died in 1895.

Ratified by the majority of states in 1865, the 13th amendment at last outlawed slavery in the US. Section one reads:

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Ratified in 1868, the 14th Amendment holds states responsible for the legal protection of all persons, regardless of race. This was a defining post-Civil War piece of legislation. Section One reads:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Sojourner Truth devoted her life to the abolition of slavery and the movement for women’s suffrage. In 1851, she delivered the following speech at a women’s convention in Akron, Ohio.

Born a Quaker in 1820, Susan Brownell Anthony led the fight for women’s suffrage until her death in 1906. Among her many activities was publishing the New York paper, The Revolution, with her ally and fellow suffragette Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The paper’s motto: “The true republic—men, their rights and nothing more; women, their rights and nothing less.”

Ratified in 1920, the 19th amendment finally opened the way to the polls for the women of the US. The text reads:

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.