username@email.com

username@email.com

In this lesson, you will learn general principles and guidelines for editing and evaluating students’ writing.

Our discussion of the final two stages of the writing process—revising/editing and proofreading—offers an entry point into a discussion of the pedagogic question of how to best engage with and respond to your students’ written work.

Your encounters with your students’ writing need to serve multiple purposes. You need to assess their progress and abilities and evaluate and grade their work. You also must be able to provide feedback and suggestions that enable your students to improve and grow as writers.

The previous lessons on principles of composition focused on how to deploy those elements effectively in your own writing. However, knowing how to write well is no guarantee of knowing how to teach others how to write well.

Your suggestions about how students can revise their writing need to explain clearly the specific improvements that students could make to their essays. You can rely on four key elements of good composition to inform and structure your comments.

Although the term revision usually describes changes to an already-written paper, students can and should begin revising their work even in its earliest stages. A teacher’s primary role while students are prewriting and outlining is to help the students articulate, refine, and focus their thoughts and ideas about their selected topic. By the time students start writing their first drafts, they should have a clear thesis statement and an organized approach.

When students come to you seeking suggestions during prewriting or outlining, it’s important to center your comments on the ideas they have brought to you and avoid inserting your own opinions and arguments into the discussion. As long as the student has not proposed a topic that is incoherent, irrelevant or inappropriate, you should concentrate on helping the student express his or her ideas in a logical, organized fashion.

Students will work harder on a paper over which they feel ownership, and the best way to engender that feeling is to make the student ultimately responsible for the paper’s content.

Once a student has handed in an initial draft of an essay, you need to expand your assessment beyond the essay’s content and begin suggesting revisions to structural and formal elements.

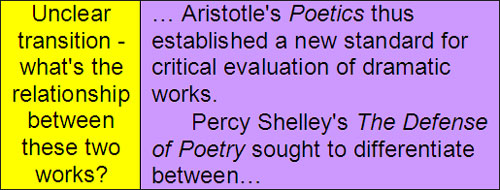

The revisions you suggest must be concrete. Isolate and discuss specific examples from a student’s essay. Instead of making a general comment at the end of a paper, such as “transitions are unclear,” you should make notes in the margins near relevant portions of the essay. Your suggestions should make clear exactly what kind of correction the student needs to make without actually making it for him or her.

When you’re reading a student’s essay for the purpose of suggesting revisions, pay particularly close attention to the presence or absence of transition words and phrases. Why? They serve as concrete, easy-to-identify markers of a larger, more abstract quality: the overall organization and coherence of ideas in an essay.

An abundance of transition words, phrases, and sentences suggests that the writer took the time and effort to think through the relationships between his or her sentences and ideas. A lack of transitional elements usually belies a hastily constructed essay with insufficient consideration to the progression of its argument.

When you’re reading a student essay with the goal of suggesting revisions, make a note in the margin to the effect of “transition needed” whenever you see consecutive sentences whose relationship is unclear.

By attempting to address this simple formal element, students will be compelled to consider larger questions of organization and argument structure. Adding transitional words and phrases also will improve the clarity and continuity of their writing.

Most of the elements of composition we have discussed so far have been most relevant to writing nonfiction. However, when suggesting revisions to a student’s work of fiction, attention to point of view is absolutely critical.

Point of view is the position or angle a writer takes relative to the subject matter of his or her writing.

A fiction writer has a choice of three basic points of view:

There are variations within each of those categories—third-person omniscient vs. third-person objective—but a student’s work of fiction should pick one of those points of view and stick with it.

Inconsistencies in point of view are a sign of a poorly constructed, disjointed work of fiction. Much like calling attention to a lack of transition words forces students to think about their essay’s organization, calling attention to shifts between different points of view forces students to unify the narrative and clarify the perspective of a work of fiction.

Not until a student has submitted the final draft of an essay is it time to evaluate and grade the student’s mastery of grammar, mechanics and the conventions of Standard English. Prior to the submission of a complete, polished essay, your primary focus should be on the content and structure of the essay.

That’s not to say that you shouldn’t mark errors in grammar and mechanics in early drafts. The only time grammar and mechanics can be completely disregarded is during prewriting, when idea generation is the sole focus.

At every other step along the way, it’s important that students be cognizant of the usage mistakes they’re making so that they have a chance to correct them. But such mistakes should only affect a student’s grade on an essay’s final draft.

When a student hands in a rough or first draft that contains grammatical and mechanical errors, you should mark the error and tell the student the source of the error or the usage rule he or she has broken.

However, with an early draft, don’t go so far as to correct the error on the page. Instead, the burden should be on the student to look up the rule and think through a suitable correction. By doing so, students will internalize and gain mastery over the rules of Standard English.

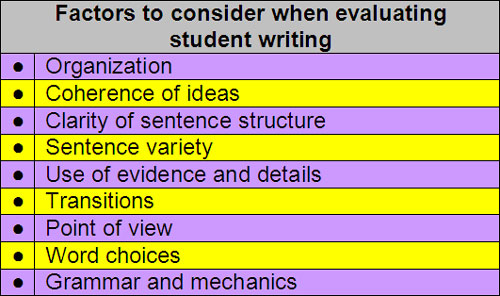

Once a student has handed in a final draft, there are myriad elements you should consider when evaluating mechanics and grammar. Specifically,

|

|

|

|

|

|

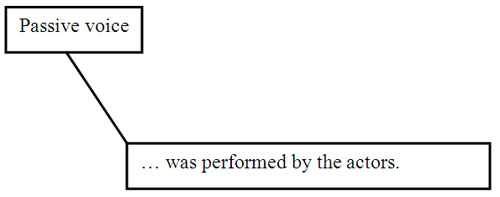

Determining the elements you emphasize in your grading depends on the audience and purpose of a piece of writing. A college essay, for example, does not need to abide by the presumption against use of the first person as strictly as, say, a formal research paper.

One final note: when you’re grading for grammar and mechanics, it’s important to develop a consistent, standardized system of copy-editing marks. You should provide your students with a key that explains these marks and use the same marking system every time you grade your students’ essays.