username@email.com

username@email.com

In this section, we’ll continue to examine how students become readers, specifically how letter knowledge, mastering conventional spelling patterns, and other skills move them closer to comprehension and fluency. We’ll also review some more phonics terms that you’ll need to know.

Students who have gotten the hang of phonemic awareness and basic phonics concepts are more likely to become successful readers than students who haven’t. Specifically, we spent some time familiarizing ourselves with how word study relies heavily on solid letter knowledge and the distinctions among implicit and explicit phonics, analogy phonics, analytic phonics, synthetic phonics, embedded phonics, and phonics through spelling.

For students to become good decoders (and, later, fluent readers), it’s imperative that they have solid letter knowledge. Knowing which phoneme corresponds with the grapheme t, for example, should be automatic. Conversely, when presented with a phoneme, such as /f/, students will be able to match it to the letter f. With more advanced letter knowledge, that student would also be able to match the /f/ phoneme with the letters gh, as in the word enough.

While kindergarten is the likely time that teachers begin working on letter knowledge, the methods can take a variety of forms. In addition to many commercial products, including software, oversized inflatable letters, and letter cards, teachers also use writing as one way of helping students gain knowledge of letters. Early writing may take the form of scribbling or drawing images that resemble letters, but with support students at this age should begin to write or draw letters.

Writing words as they sound can help children get a tighter grasp on the phoneme-grapheme connection. The physical act of writing may be harder for some students than others due to differences in motor-skill development rates, but instructors can use letter blocks or letter cards like the ones below to facilitate easier word construction.

Letter Cards

Of course, assessing the student’s mastery of any skill is important. There are many rubrics for letter-knowledge assessment available, and instructors also use more informal approaches. For example, the teacher may hold up a series of letter flashcards and ask the student to identify the letter on the card. The teacher may also ask the student to produce the phoneme that matches the letter on the card. Performing this test and recording the results several times during the school year will give the teacher a sense of how each student is progressing.

Working on conventional spelling patterns is also important to decoding and eventual fluency. Again, there are a vast number of methods out there, but let’s look at a simple one that uses the student’s prior knowledge.

Using three words that the student already knows, create a simple chart like this one:

| Get | Cat | Cake |

|---|---|---|

After creating the chart, you may introduce the idea that spelling uses patterns—this will depend on the individual student. Have the student fill in the chart with other words that have the same rime, like this:

| Get | Cat | Cake |

|---|---|---|

| set | fat | bake |

| bet | hat | make |

Depending on the student’s penmanship ability, you could make word cards that they place in the chart. For example:

It’s important to have some fluency when analyzing words. For example, you should be able to name the basic parts of a word—affix, syllable, onset, rime—quickly and effortlessly.

What is the rime of the second syllable of the word below?

Answer D is correct. In this case, -ent is the rime of the second syllable. Its onset is the consonant m. Click here to review onsets and rimes.

Phonics is a powerful way to reach the students who need your best efforts in direct instruction, while ensuring that the “naturals” really are “getting it.”

Let’s examine some of the terms and techniques that you’ll need to know for effective phonics instruction.

When a lady with a chocolate bar turns a corner and collides with a gentleman who is holding an open container of peanut butter, the resultant confection is a blend. You will still see and taste the chocolate, and you will still see and taste the peanut butter. Blending them together creates a synergistic whole that is somehow greater than the sum of the parts. Nonetheless, you have not taken away any of the properties that distinguish the chocolate from the peanut butter.

So it is with consonant blends. Two or three letters come together to form a phonemic blend, but the sounds that distinguish one letter from the other remain. In the word stray, for instance, one can discern the individual phonemes /s/, /t/, and /r/, yet they are blended together like chocolate, peanut butter, and graham crackers. An easy mnemonic goes like this: “Blend is a word that contains two blends.”

Take a look at the word above. Consonant blends (also called consonant clusters) may appear at the beginning of a word, within the middle of a word, and/or at the end of a word. For instance, in the word flagrant, there are three consonant blends: fl, in which one can clearly hear both constituents, /f/ and /l/; gr, in which the /g/ and /r/ sounds are still distinguishable; and nt, which allows the voices of both the /n/ and the /t/ to be heard.

Of course, not all unions of consonants permit the members to maintain their individuality. There are some couples who surrender their individuality and produce a totally different sound altogether. These, you may remember, are called digraphs. Click here to review them.

Please keep in mind that any discussion of representing phonemes is secondary to the primary objective of drawing the desired sounds out of letters and letter combinations that appear in words. Recognizing the various forms that appear in written English will help students draw sounds from written words, blend those sounds, and arrive at the intended word. This process is called decoding.

One of the big two competencies for successful reading is decoding. The other is comprehension; let’s see how the two are related.

Decoding means that the student is able to divine a word from a group of letters. This can be done through the processes that are systematically and explicitly taught to students by their teachers. Those processes, in turn, rely upon the discrete lessons and strategies with which the reader is equipped, specifically for the purpose of being able to decode words. Let’s try some decoding ourselves. Check out the following word:

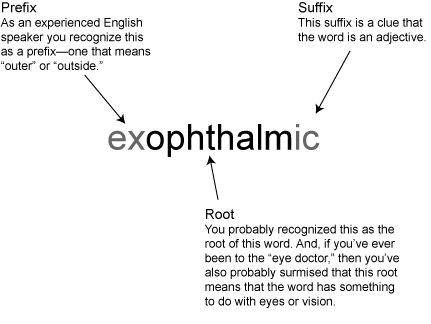

Whether you can comprehend this word is beside the point, at least during the decoding process. You undoubtedly recognize it as a word and can break it down into its component parts (prefix, root, suffix).

Once a word is pulled from the decoding process, the reader’s ability to comprehend spoken language will allow him or her to extract meaning from the word that he or she just decoded. That is, decoding turns a written word into a spoken word; and if the student is not familiar with the word that was just decoded, then the comprehension part of the equation has failed to produce a mental image for the reader.

Of course, encountering a certain percentage of indecipherable words will frustrate the reader. Such texts are considered beyond the reader’s independent reading level. A picture book would probably be accessible to younger readers—or older readers who have not yet mastered the decoding process, but specialized texts (like astrophysics) would probably not be accessible to these readers.

The adjective exophthalmic, by the way, means “characterized by the prominence of the eyeballs.”

Etymology is the study of word origins, as well as the different meanings the word has had throughout its history. Etymology is taught explicitly, as the meanings of roots are not always intuitive. Explicit word study is the vehicle for teaching etymology, and word study is virtually impossible without the prerequisite mastery of sound-letter relationships.

The student who has gained a firm grip on a family of roots is now equipped to both decode and comprehend derivatives of those roots.

The study of the prefixes and suffixes that one might tack onto these roots is called morphology, which is also addressed later in this lesson.

Morphology is a close cousin of etymology. You’re already familiar with the root of the word, {morph}, which refers to change or derivation. The morpheme {-ology} refers specifically to the science or study of something, in this case, changes or derivatives of words with reference to the relationships among roots, prefixes, and suffixes.

When discussing morphology, it is important to note that a morpheme can be as little as a single letter, provided that the letter contains or imparts meaning. For instance, in the word morphemes, the {morph} has its own meaning, as noted above. The {-eme} also contains its own meaning, “a discrete unit of linguistic structure,” a la morpheme, phoneme, grapheme, etc. The morpheme {-s}, as attached to the end of a word, is the Great Pluralizer. This single letter imparts meaning, namely “more than one.”

Let’s take another look at exophthalmic, this time adding some annotations:

Let’s use two disciplines that we’ve discussed previously (morphology and analytic phonics) to investigate the meaning of orthography.

The morpheme {ortho} means “correct,” and the morpheme {-graphy} means something to the effect of “to write.” Put them together, and you get the meaning “to write correctly.” However, orthography isn’t about the physical act of writing; it’s about spelling and the conventions that govern how we spell.

The analytic phonics approach is more fun, as is often the case. As an adult, you’re probably familiar with other words that incorporate {ortho}. I’m thinking orthodontist, orthotics, and orthopedics. I already know how to pronounce {ortho}, but thinking of analogous terms helps me crack the meaning. All of the terms orthodontist, orthotics, and orthopedics, refer to straightening things out, be they teeth, feet, or joints. The {graphy} part is even more common, appearing in ethnography (writing about race), graphite (pencil lead), biography (writing about one’s life), grapheme (written representation of a phoneme), and autograph (signing one’s own name). We again get “straight writing,” or “correct spelling.”

By explicitly teaching the correct spelling of words—particularly irregular words—you’re building the students’ awareness of spelling conventions. When used in combination with morphology and etymology, the students’ opportunities for “getting it” are exponentially increased.

The inspiration behind many of Dr. Seuss’s books was the objective of writing books that used a limited vocabulary of short, decodable words in anticipatable, rhyming stories. Even in novels for adults, a surprisingly significant percentage of the words are among the one hundred or so most common words in the English language.

Directly teaching students to recognize many of these frequently used words brings a two-fold benefit: it quickens the pace of reading and eases the sounding out process in the case of words that are often difficult for children to sound out.

Automaticity with regard to the most common words helps move a reader along at a quicker pace. Getting from the initial capital at the beginning of a sentence to the period at the end can be a slow struggle. If the student is not spending valuable time trying to figure out words like if, the, is, not, to, and, and out, then he or she will finish the sentence with some idea of what the key words in the sentence were trying to communicate.

The secondary reason for drilling (that’s not always a bad word) students on sight words is that many such words do not lend themselves to being sounded out. For example, of can reasonably be decoded as “off.” The word to all too easily could become “toe.” Some kids would naturally assume that one is “own” and that sure is “sewer.”

The quick-and-dirty analogy goes like this: If I were not able to type with automaticity, I would use too much of my brain power simply trying to find the keys on the keyboard. Equipped with some keyboarding skill, however, I can concentrate on the subject matter and won’t be tempted to shortchange you, dear reader, by being overly parsimonious with the analogies. Appropriate drilling, then, is an investment in skills that will permit students to perform simple addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, decoding, and sight reading without obscuring higher-order objectives.

It is tempting to declare that spelling conventions belong in the writing domain only and should not be addressed until some point after students have gained confidence in their writing ability through phonetic spelling. In this, as in many cases, the intermingling of writing and reading points to the utility of teaching spelling conventions in order to enhance the students’ decoding ability.

Of course, as you encourage your students to write, your focus will not be holding them accountable for spelling, grammar, or punctuation. Initially, you’ll want to prevent writer apprehension by emphasizing the importance of getting ideas and stories onto the paper. Later in the year, as the students mature into imaginative writers, you can begin to introduce editing conventions one at a time.

This is where your efforts with sight words and word walls will pay off. It’s where phonics through spelling becomes more interesting for both you and the students.

The conventions that appear frequently in monosyllabic words and within polysyllabic words lend themselves to explicit instruction on conventions. For instance, in monosyllabic words that have a short vowel sound, the spelling will be a vowel-consonant combination (or VCC), perhaps with another consonant tacked onto the end, as in tack, a VCC word. When those same VC words are turned into adjectives—that is, when they end in what sounds like a long e—the final consonant is doubled before adding the final {-y}, as in sap’s transformation into sappy. Since tack and other VCC words already have that extra consonant at the end, it is only necessary to add the final {-y}.

Word study often incorporates a strategy known as a word sort. Word sorts provide students with an opportunity for guided practice and independent practice, but they require that students have mastered the ability to identify letters as vowels or as consonants, to sort like items, and to recognize patterns that appear in like words. Like words, in this case, may refer to words that end in VC (vowel-consonant) or VCC. The discussion of spelling conventions in this module provides an example of generalized conventions that are conducive to word sorts, and vice versa.

Which of the following phonics concepts emphasizes roots, prefixes, and suffixes?

Choice A is the correct answer. Remember that morphemes are those packets of meaning that can either be a root, a prefix, or a suffix, and can be as short as a single letter. Choice D refers to correct spelling.

Which of the following involves drills intended to support automaticity with common words?

Choice B is the correct answer. Sight words are the most common one hundred or so words, the ones that typically represent half or more of elementary texts. Students who have mastered a large number of sight words will not waste time figuring them out and will have completed reading a sentence with some sense of what the more important words were trying to say.

Which of the following best describes etymology?

Choice D is the correct answer. Some familiarity with the Latin or Greek roots of larger words often allows students to figure out the meaning of multiple forms of the word. Taken together with morphology, which ties etymology to the study of morphemic prefixes and suffixes, etymology is a powerful tool for building one’s vocabulary.